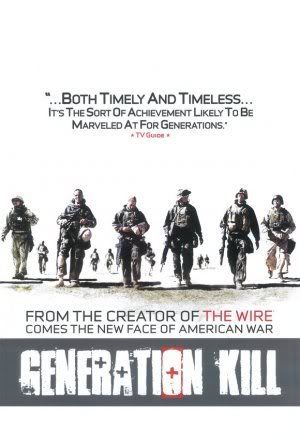

Proof that "Generation Kill", the miniseries produced by HBO films and written by David Simon and Ed Burns, their first project after the end of their television landmark "The Wire", a series which is completely incomparable in quality and scope to anything which has come before or since, is too intelligent to be concerned with simplistic political sloganeering, blind patriotism, or taking an anti-militaristic stance is the reaction which the political extremes have had to it. Any person with far right views I've spoken to or read on the internet has said similar things: this movie emasculates the marines and turns them into bleeding heart liberals (presumably because the film, and I will be referring to this as a film from this point onwards because it's definitely as much a film as "Berlin Alexanderplatz" is, has the guts to portray them as having compassion for wounded or killed civilians), and any person with far left views I've spoken to has apparently found the film to be immoral, presumably because it portrays men who spew violent, racist, homophobic, and misogynist invective as human beings.

Proof that "Generation Kill", the miniseries produced by HBO films and written by David Simon and Ed Burns, their first project after the end of their television landmark "The Wire", a series which is completely incomparable in quality and scope to anything which has come before or since, is too intelligent to be concerned with simplistic political sloganeering, blind patriotism, or taking an anti-militaristic stance is the reaction which the political extremes have had to it. Any person with far right views I've spoken to or read on the internet has said similar things: this movie emasculates the marines and turns them into bleeding heart liberals (presumably because the film, and I will be referring to this as a film from this point onwards because it's definitely as much a film as "Berlin Alexanderplatz" is, has the guts to portray them as having compassion for wounded or killed civilians), and any person with far left views I've spoken to has apparently found the film to be immoral, presumably because it portrays men who spew violent, racist, homophobic, and misogynist invective as human beings.In fact, "Generation Kill" is the farthest thing from either celebrating the military or being anti-militaristic. Like on "The Wire", David Simon and Ed Burns are on the side of the working class, as Kent Jones in Film Comment points out, and they have no interest in making a moral judgment on the nature of the work they're portraying, whether it's teaching, politics, drug dealing, or invading a country. Like Simon went beyond portraying drug dealers on "The Wire" to transporting us to their world and showing us their own problems, their own moral standards, their own worries and concerns, and introduced us to their own vernacular, he does the same with the marine corps in "Generation Kill". Like "The Wire", this is cunning and clever drama: it is political without taking sides, concerned with the inefficiency and bad planning coming 'from above' but without putting the blame on any individuals. It portrays people, some less likable and morally or politically correct than others, but people.

The only thing keeping "Generation Kill" from truly being a military version of "The Wire" is that its comparatively limited scope- it takes place within the first, 'triumphant' week of the invasion, and focuses pretty much only on one group of people. I'm entirely convinced that Simon could have written a thoroughly engrossing and fascinating drama about the Iraq war which extended past these five days, one which would have taken us past the marine corps into the lives of the other military units involved in the invasion, and the higher-ups as well, as he did starting in season 3 in "The Wire". As it stands, this is not a limitation of the power which "Generation Kill" holds, but a masterstroke in its success of making its point: every element which has made the situation in Iraq so chaotic was present in a latent form from the beginning. The film is not even really making a moral judgment of the war in Iraq, if anything it supports a well-executed version of it: most of the Iraqis we see, nearly 90% of them, are incredibly grateful, at least at this early stage, for being relieved of Saddam's rule.

Moreover, no American marine or any Iraqi is portrayed simplistically as a 'bad guy' or 'good guy', not even the bloodthirstiest of the Americans, and this writing is brought to life admirably well by the mostly perfect cast and the excellent direction and production value (it is obviously not a big-budget Hollywood film, but it still achieves real authenticity in almost every regard- the closest I came to disbelieving it was when a few Iraqis were portrayed as darker-skinned than any I've seen). The closest thing to a villain in the film is Saddam himself, who makes no literal appearance outside of posters on the streets, but then again he is pretty much the closest thing to a movie 'bad guy' in reality.

"Generation Kill" is, like "The Wire", ultimately a workplace drama about workplace politics. That the stakes are higher and that the innocent are killed even more often than they are on "The Wire" is irrelevant to the writers. This may make "Generation Kill" boring to those accustomed to and expecting a more standard war film, one which attempts an anti-war or pro-war statement. Like "The Wire" again, what the viewer is left with in the end is only a dislike of unnecessary violence and casualties, and a portrayal of the toll they take on those involved in either perpetrating the violence or those related to the victims. Both "The Wire" and "Generation Kill" are dramatically built on disappointment and disillusionment with the system in place itself, and like "The Wire" it is all about bad decisions, mistakes, and the rare good decision. The film ends with a montage and a song, much like every season of "The Wire", and with its subtle summation of the hours gone by and its emotional impact it cements David Simon's status as one of the greatest and most important writers of our time.